Memory Consolidation: How Stress Develops After Exposure To A Traumatic Event And What Can Be Done to Reduce It

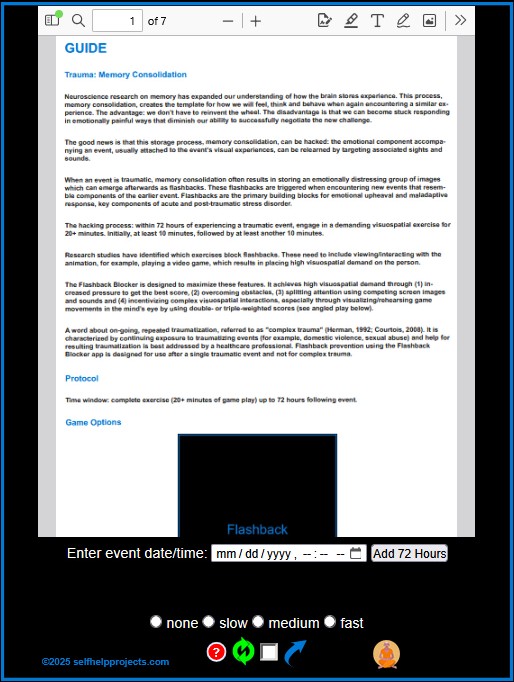

Within a 72-hour time window of the event: 20+ minutes game play

Prefaced by recall of disturbing images from the event

Maximizing visuospatial interactions

Result: preventing intrusive memories of the event

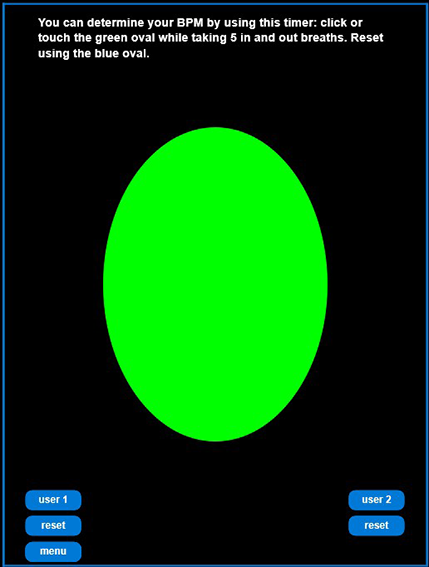

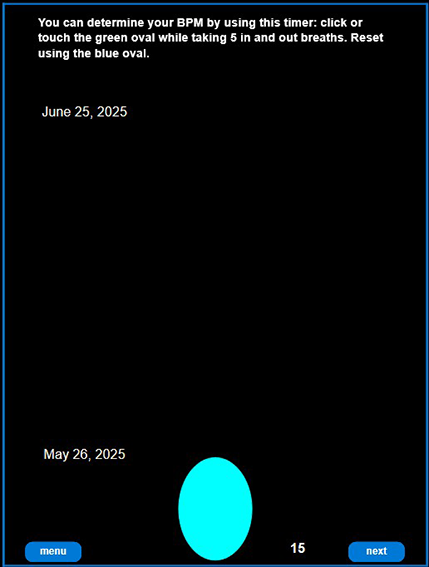

free prevention app: mobile browser version (touch-screen)

free prevention app: desktop browser version (mouse-enabled-screen)

In the hours immediately following exposure to a traumatic event, memory consolidation, including imagery and associated emotional learning occurs. These can harden into intrusive memories, primarily images, but also as smells, sounds, other sensations, that later progress and trigger distress. On a continuum, subsequent distress ranges from mild but upsetting levels, through “subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder” features affecting social/work spheres and suicidality (Zlotnick et al., 2002) all the way to full-blown acute and posttraumatic stress disorders.

A growing body of research (James et al., 2015; Kessler et al., 2018; Kessler et al., 2019a; Kessler et al., 2019b; Iyadurai et al., 2019; Kanstrup et al., 2021; Thorarinsdottir et al. 2022; Singh et al., 2022) is showing that targeting and preventing the early formation of intrusive memories immediately after exposure to a traumatic event, using principles derived from memory consolidation studies, can significantly reduce distress and its progression, “nipping it in the bud.”

(1) 20+ minutes of interacting with an online animation (for example, game play) (2) including visuospatial exercises (pattern matching, visualizing pieces in one’s mind as preparation for moving them where needed by game rules, then executing the movement), (3) within a time window of 72 hours or less, (4) targeting event hotspots (Gray & Holmes, 2008), can (5) reduce intrusive memories of disturbing imagery.

This approach targets a critical element, intrusive memories, implicated in subsequent development of disturbing levels of stress following exposure to a traumatic event. Most often experienced as images, these can also be sounds, smells, other triggering sensations. Intrusive memories can be experienced within current reality: they intrude as recall of a past, not current event. A subset of intrusive memories, flashbacks, dissociative experiences during which the person feels like they are reliving the events at the time they occurred, can blur this past-present time distinction.

A game like Tetris is often used in these research studies and includes the needed visuospatial animation exercises. Before engaging in the game play, a critical element is for the user to recall hotspots, disturbing images from the event (Grey et al., 2008), Hoppe, et al., 2022). They are instructed to focus on the complex mental movement of game pieces (mind’s eye perspective), a critically necessary component. Then, play for a minimum of 10 minutes, plus additional game play totaling 20+ minutes, within the 72-hour time window. Booster sessions following the same protocol while optional (Kanstrup et al., 2021), in our opinion are useful: in our adaptation of the protocol, the “+” in “20+ minutes”.

A variety of game animations featuring visuospatial-based interaction, including explicit instructions to visually rehearse then move pieces, can be used since the goal is for the user to experience the type of interactions, including visuospatial movement, which have been shown to prevent subsequent intrusive memories.

Based on research testing game animations that do not produce positive results consistent with recent research (James et al., 2015; Asselbergs et al., 2018), we hypothesize that their design may not sufficiently draw user-attention to the visuospatial component. This must be explicit in the instructions delivered to users (Singh, 2022). “Critically [emphasis added], participants were asked to ‘try to work out in your mind’s eye where best to place and rotate these [Tetris] blocks in order to make as many complete horizontal lines as you can and get the best score’ (Lau-Zhu et al., 2017). “The emphasis on mental rotation is key to ensure that the visuospatial demand of Tetris gameplay is maximised, as greater visuospatial demand has been associated with fewer subsequent intrusive memories…” (Kanstrup et al., 2020).

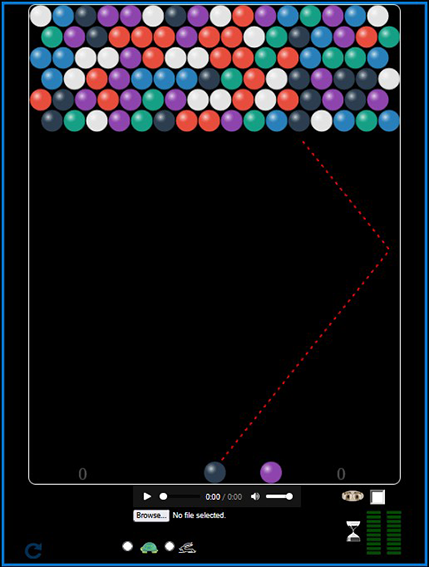

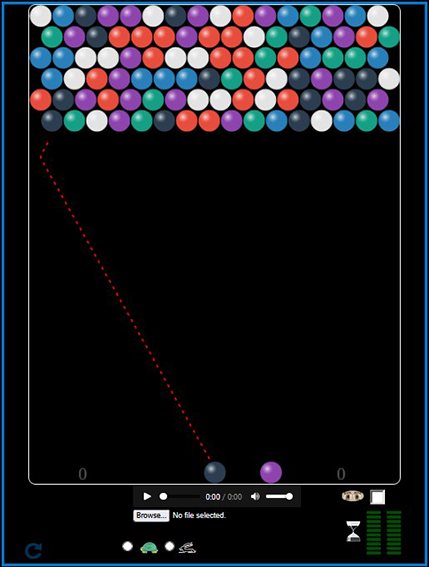

Concurrently (1) seeing the next game piece to encourage next-move planning/visualization, (2) encouraging angled play (see images below) incentivized by doubling or tripling a successful shot’s point score when angled play is used, (3) viewing a timer bar timing-out the current screen (desktop version), (4) adding options for bilateral eye movement and sound and (5) achieving high overall scores all serve to split the user’s attention and increase visuospatial demand.

Another type of research result similarly demonstrated less frequency of intrusive memories but not reduced intensity. This research design using Tetris raised the question whether reducing the frequency of intrusive memories, which was demonstrated in this and other studies, is as helpful as reducing their intensity. Intensity, not measured in other studies, was measured in this study and did not occur. The research study’s authors also noted study limitations including differences between their sample population, who were exposed to a trauma film (see James, et al., 2016), and sample populations in other studies who had been exposed to real-life trauma events (Badawi, et al., 2022).

A research study done to determine if “proactive” playing of a game animation, prior to exposure to a trauma event (film), is helpful, reported the following: there were no differences in intrusive memory frequencies between a control group and the group using the intervention (James et al., 2016b). It appears that cognitive inoculation prior to event exposure does not produce positive results.

While there is emerging research evidence for the efficacy of the approach delivered in the time-window following an event, that includes explicit attention by subjects to visuospatial visualization and manipulation, researchers often qualify results with the need for more research in order to conclusively demonstrate usefulness, as well as better determine which features need to be included/maximized to achieve the best results.

With this in mind, as well as the adage ‘the perfect need not be the enemy of the good,’ plus the overall safety of these strategies (when following safe-use protocols), we have made a game animation, Flashback Blocker. It is available to potential users who are encouraged to weigh the pro’s and con’s of utilizing it.

A word about on-going, repeated traumatization, sometimes referred to as “complex trauma” (Herman, 1992; Courtois, 2008). It is characterized by continuing exposure to traumatizing events (for example, domestic violence, sexual abuse) and help for resulting traumatization is best addressed by a healthcare professional. Flashback prevention using the Flashback Blocker app is designed for use after a single traumatic event and not for complex trauma.

The Flashback Blocker web app is available in a desktop, mouse-enabled version and a mobile, touch-enabled version (links above). It can be self-administered following our adapted protocol (viewable in the app or as a downloadable PDF). It’s active ingredients can be distilled down to high visuospatial demand increased by a user’s motivation to get the highest possible score in the shortest time or before added obstacles end the game.

Options include slow or fast timer bars to advance the screen if a choice is not timely and optional audiovisual distractors (please note use cautions in the PDF protocol for people with disorders affecting their seizure threshold) to strengthen a key memory consolidation-blocking element: split-attention (see images below).

right-side angled play, earning double scoring, to improve visuospatial effects

left-side angled play, earning triple scoring, to improve visuospatial effects

Stress Reduction

The Flashback Blocker app includes a breath pacing tool that can be used before, during or after the primary exercise to reduce stress. Further information and use guidelines can be found in the help PDF.

After the 72-hour event-exposure time window (the time during which memory consolidation occurs), disturbing effects of acute or posttraumatic stress, if experienced, can be reduced through activating memory reconsolidation.

Resources

Download Chakra mp3’s for use with bilateral sound feature in the Flashback Blocker: right-click/touch, “save as” to location on device, then use the feature’s “browse” button to open/play the saved sound.

References

Asselbergs, J., Sijbrandij, M., Hoogendoorn, E., Cuijpers, P., Olie, L., Oved, K., Merkies, J., Plooijer, T., Eltink, S., & Riper, H. (2018). Development and testing of TraumaGameplay: An iterative experimental approach using the trauma film paradigm. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), Article 1424447. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1424447.

Badawi, A., Berle, D., Rogers, K., & Steel, Z. (2020). Do cognitive tasks reduce intrusive-memory frequency after exposure to analogue trauma? An experimental replication. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(3), 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702620906148.

Badawi, A., Steel, Z. & Berle, D. (2022). Visuospatial Working Memory Tasks May Not Reduce the Intensity or Distress of Intrusive Memories. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 13. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.769957.

Courtois, C. A. (2008). Complex Trauma, Complex Reactions: Assessment and Treatment. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 2008, Vol. S, No. 1, 86–100.

Grey N., Holmes E.A. (2008). “Hotspots” in trauma memories in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A replication. Memory. 2008;16:788–796. [PubMed: 18720224].

Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A Syndrome in Survivors of Prolonged and Repeated Trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, Vol. 5, No. 3, 1992.

Holmes, E. A., James, E. L., Coode-Bate, T., & Deeprose, C. (2009). Can Playing the Computer Game “Tetris” Reduce the Build-Up of Flashbacks for Trauma? A Proposal from Cognitive Science. PLoS ONE 4(1): e4153. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004153.

Holmes, E. A., James, E. L., Kilford, E. J. & Deeprose, C. (2010) Key Steps in Developing a Cognitive Vaccine against Traumatic Flashbacks: Visuospatial Tetris versus Verbal Pub Quiz. PLoS ONE 5(11): e13706. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013706.

Holmes, E. A., James, E. L., Killford, E. J., & Deeprose, C. (2012). Correction: Key Steps in Developing a Cognitive Vaccine against Traumatic Flashbacks: Visuospatial Tetris versus Verbal Pub Quiz. PLOS ONE 7(11): 10.1371/annotation/eba0a0c8-df20-496b-a184-29e30b8d74d0. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/annotation/eba0a0c8-df20-496b-a184-29e30b8d74d0.

Holmes, E. A., Hales, S. A., Young, K., & Di Simplicio, M. (2019). Imagery-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder and mood instability. The Guilford Press.

Hoppe, J.M., Walldén, Y.S.E., Kanstrup, M., Singh, L., Agren, T., Holmes, E.A., Moulds, M.L. (2022). Hotspots in the immediate aftermath of trauma – Mental imagery of worst moments highlighting time, space and motion. Conscious Cogn. 2022 Mar;99:103286. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2022.103286. Epub 2022 Feb 24. PMID: 35220032.

Lau-Zhu, A., Holmes, E.A., Butterfield, S., Holmes, J. (2017). Selective Association Between Tetris Game Play and Visuospatial Working Memory: A Preliminary Investigation. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2017 Jul-Aug;31(4):438-445. doi: 10.1002/acp.3339. Epub 2017 Jul 12. PMID: 29540959; PMCID: PMC5836929.

Iyadurai L., Blackwell, S. E., Meiser-Stedman, R., Watson, P. C., Bonsall, M.B., Geddes, J, R., De Ozorio Nobre, A. C. & Holmes, E. A. (2017). Preventing Intrusive Memories after Trauma via a Brief Intervention Involving Tetris Computer Game Play in the Emergency Department: A Proof-of-Concept Randomized Controlled Trial. Mol Psychiatry. 2017 Mar 28.

Iyadurai, L. et al. (2019). Intrusive memories of trauma: a target for research bridging

cognitive science and its clinical application. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 69, 67–82

(2019).

James, E. L., Bonsall, M. B., Hoppitt, L., Tunbridge, E. M., Geddes, J. R., Milton, A. L., & Holmes, E. A. (2015). Computer Game Play Reduces Intrusive Memories of Experimental Trauma via Reconsolidation-Update Mechanisms. Psychological science, 26(8), 1201–1215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615583071.

James, E. L., Lau-Zhu, A., Clark, I. A., Visser, R. M., Hagenaars, M. A., & Holmes, E. A. (2016a). The trauma film paradigm as an experimental psychopathology model of psychological trauma: Intrusive memories and beyond. Clinical Psychology Review, 47, 106–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.010.

James, E. L., Lau-Zhu, A., Tickle, H., Horsch, A., & Holmes, E. A. (2016b). Playing the computer game tetris prior to viewing traumatic film material and subsequent intrusive memories: Examining proactive interference. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 53, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.11.004.

Jiang, C., Chen, W., Tao, L., Wang, J., Cheng, K., Zhang,Y., Qi Z and Zheng, X. (2023). Game-matching background music has an add-on effect for reducing emotionality of traumatic memories during reconsolidation intervention. Front. Psychiatry 14:1090290. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1090290.

Kanstrup, M., Kontio, E., Geranmayeh, A., Olofsdotter Lauri, K., Moulds, M. L., & Holmes,

E. A. (2020). A single case series using visuospatial task interference to reduce the

number of visual intrusive memories of trauma with refugees. Clinical Psychology &

Psychotherapy, 28(1), 109-123. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2489.

Kanstrup, M., Singh, L., Göransson, K.E. et al. (2021). Reducing intrusive memories after trauma via a brief cognitive task intervention in the hospital emergency department: an exploratory pilot randomised controlled trial. Transl Psychiatry 11, 30 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-01124-6.

Kessler, H., Holmes, E. A., Blackwell, S. E., Schmidt, A.-C., Schweer, J. M., Bücker, A., Herpertz, S., Axmacher, N., & Kehyayan, A. (2018). Reducing intrusive memories of trauma using a visuospatial interference intervention with inpatients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(12), 1076–1090. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000340

Kessler, H., Schmidt, A.-C., James, E.L., Blackwell, S.E., von Rauchhaupt, M., Harren, K., Kehyayan, A., Clark, I.A., Sauvage, M., Herpertz, S., Axmacher, N., Holmes, E.A. (2019a). Visuospatial computer game play after memory reactivation delivered three days after a traumatic film reduces the number of intrusive memories of the experimental trauma, Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry (2019), doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2019.01.006.

Kessler, H., Dangellia, L., Kessler, R., Mahnke, V., Herpertz, S., & Kehyayan, A. (2019b). Mobilum-a new mobile app to engage visuospatial processing for the reduction of intrusive visual memories. mHealth, 5, 49. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2019.09.15.

Lau-Zhu, A., Holmes, E.A., Butterfield, S., Holmes, J. (2017). Selective Association Between Tetris Game Play and Visuospatial Working Memory: A Preliminary Investigation. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2017 Jul-Aug;31(4):438-445. doi: 10.1002/acp.3339. Epub 2017 Jul 12. PMID: 29540959; PMCID: PMC5836929.

Singh, L., Kanstrup, M., Gamble, B., Geranmayeh, A., Göransson, K.E., Rudman, A., Dahl, O., Lindström, V., Hörberg, A., Holmes, E.A., Moulds, M.L. (2022). A first remotely-delivered guided brief intervention to reduce intrusive memories of psychological trauma for healthcare staff working during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2022 Apr;26:100884. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2022.100884. Epub 2022 Jan 12. PMID: 35036626; PMCID: PMC8752164.

Thirkettle, M., Lewis, J., Langdridge, D., Pike, G. A Mobile App Delivering a Gamified Battery of Cognitive Tests Designed for Repeated Play (OU Brainwave): App Design and Cohort Study. JMIR Serious Games 2018;6(4):e10519. doi: 10.2196/10519

Thorarinsdottir, K., Holmes, E.A., Hardarson, J., Stephenssen, E.S., Jonasdottir, M.H., Kanstrup, M., Singh, L., Hauksdottir, A., Halldorsdottir, T., Gudmundsdottir, B., Thordardottir, E., Valdimarsdottir, U., Bjornsson, A. Using a Brief Mental Imagery Competing Task to Reduce the Number of Intrusive Memories: Exploratory Case Series With Trauma-Exposed Women. JMIR Form Res. 2022 Jul 20;6(7):e37382. doi: 10.2196/37382. PMID: 35857368; PMCID: PMC9491830.

Yackle, K., Schwarz, L. A., Kam, K., Sorokin, J. M., Huguengard, J. R., Feldman, J. L., Luo, L. & Krasnow, M. A. (2017). Breathing control center neurons that promote arousal in mice. Science 355, 1411–1415.

Yu, Y., Zhang, X., Xue Y, Ni S. (2024). Reducing intrusive memories and promoting posttraumatic growth with Traveler: A randomized controlled study. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 2024;16(4):2283.

Zlotnick C, Franklin CL, Zimmerman M. (2002). Does “subthreshold” posttraumatic stress disorder have any clinical relevance? Compr Psychiatry. 2002 Nov-Dec;43(6):413-9. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.35900. PMID: 12439826.

Loading

Loading